I’ll admit that I’m pretty ignorant when it comes to botanical history. When I took systematic botany back in the ’70s, it was all about the flowers. While no pro, I was pretty good at dissecting them, and with Gleason and Cronquist by my side, keying plants out to species.

I’ll admit that I’m pretty ignorant when it comes to botanical history. When I took systematic botany back in the ’70s, it was all about the flowers. While no pro, I was pretty good at dissecting them, and with Gleason and Cronquist by my side, keying plants out to species.

It made perfect sense to me that the sexual parts of plants would correspond precisely with their evolutionary history, though we were warned that with advances in DNA analysis, we might find a few surprises in our (for the most part) neat and clean schema. At least that was an easy sell to 20-year-old without much plant experience.

It’s also easy for a 20-year-old to think that this focus on flower parts must have been easy to figure out. Boy was I wrong. And wading through Anna Pavord’s The Naming of Names showed me just what a long slow journey it’s been.

I won’t try to retrace the journey Pavord leads from Theophrastus to John Ray — from trying to make sense of plants from gross morphology or use their use as food, medicine or magic to what we ‘know’ today. Let’s just say it’s not a trip for the faint of heart. I agree with Publishers Weekly: “Pavord’s prose dazzles, but it’s not enough to carry readers with a casual interest in plants or gardening through an otherwise dense history.”

But a few thoughts crossed my mind as I read:

Of the nearly 60 cast members in this epic, I don’t recall a single woman. Yes, women were largely excluded from academic circles from the Greeks through the Rennaisance. (There is mention of apothecaries and ‘herbarists’, but they all sounded like semi-licensed men to me.) I have a hard time believing that there wasn’t a parallel network of midwives and healers who maybe didn’t quest to categorize the entire plant kingdom, but knew well the plants that grew where they lived — and knew how to use them.

Linnaeus doesn’t appear until the epilogue. Seems the plate was set for him by those who came before, and he just picked the low-hanging fruit. (Even though he’s the one name that all young botanists know.) But Pavord does include this delightful quote from that randy Swede:

The actual petals of a flower contribute nothing to generation, serving as the bridal bed which the great Creator has so gloriously prepared, adorned with such precious bedcurtains and perfumed with so many sweet scents, in order that the bridegroom and bride may herein celebrate their nuptials with the greater solemnity.

The Bishop of Carlisle fears his system will ‘shock female modesty’ with its ‘gross prurience’. So I guess we’re not the only ones living in an era where the quest for truth is hampered by those who are unwilling to deal with the sexual nature of the natural world.

The Bishop of Carlisle fears his system will ‘shock female modesty’ with its ‘gross prurience’. So I guess we’re not the only ones living in an era where the quest for truth is hampered by those who are unwilling to deal with the sexual nature of the natural world.

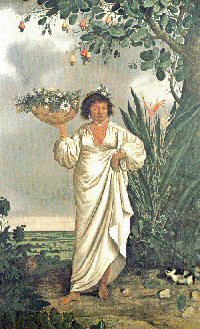

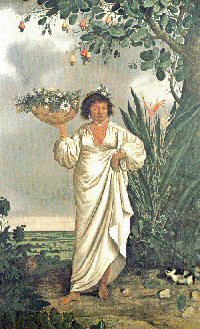

I’ve always been fascinated by botanical illustration, and there are many great ones included. They parallel and support the text quite well. You can almost get the gist of the book by just studying the pictures.

The two I’ve included here are not typical, but they’re the ones I fell in love with. They are by Albert Eckhout, a Dutch painter who accompanied an expedition to northeast Brazil from 1637 to 1644. His paintings document the wonderful new plants that came to Europe from the New World, and forced botanists to come up with a system of classification that would work for them as well.

I also found myself sympathizing with the early botanists trying to sort through synonyms before standardized naming. I’m working on a Vegetable Varieties for Gardeners website at my day job. We’ve got more than 5,000 varieties described, and there are more to come. The trouble is, those selling seeds aren’t always the most thorough and careful in their naming and descriptions, especially when it comes to heirlooms and cultivars from other cultures. While we’ve got a good start at the site, it would be a full time job to just sort through them all to find all the instances when two differently named varieties are actually the same thing. Or two varieties with the same name are actually significantly different.

Stop by that site and look for something new to grow this year, or rate and review some of your favorites.

I’ll admit that I’m pretty ignorant when it comes to botanical history. When I took systematic botany back in the ’70s, it was all about the flowers. While no pro, I was pretty good at dissecting them, and with Gleason and Cronquist by my side, keying plants out to species.

I’ll admit that I’m pretty ignorant when it comes to botanical history. When I took systematic botany back in the ’70s, it was all about the flowers. While no pro, I was pretty good at dissecting them, and with Gleason and Cronquist by my side, keying plants out to species.